Summits | Meetings | Publications | Research | Search | Home | About the G7 Research Group

Follow @g7_rg

|

Summits | Meetings | Publications | Research | Search | Home | About the G7 Research Group Follow @g7_rg |

|

100 Days Mission to Respond to Future Pandemic Threats

Report submitted to the G7 Cornwall Summit, June 12, 2021

[pdf]

Imagine a scenario where COVID-19 had hit, but the world was ready. A scenario where:

We had a sophisticated international surveillance network that alerted the world to some unusual cases of "flu" in Wuhan, China in December 2019, that was able to share the genomic sequence and disease information even quicker than the 20 days it took.

A responsive diagnostics sector swung into action, producing accurate and rapid diagnostic tests at scale to detect new cases early, monitor contacts, and guide critical public health intervention.

The research and development had already been completed and prototype diagnostics and therapeutics only needed tweaking before they could be subjected, along with vaccines, to rapid assessment through an established international clinical trials network to quickly affirm their safety and efficacy.

Global manufacturing capacity was there and swiftly activated, ready to produce accurate diagnostics quickly and therapeutics and vaccines at scale to those who need them.

The World Health Organization (WHO), upon declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), enacted agreed protocols setting out the 'rules of the road' for a pandemic, speeding up data sharing and regulatory approvals and triggering procurement pools for diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines (DTVs).

There was sufficient financing available, and ready to draw down, to get DTVs to the poorest countries at the scale needed.

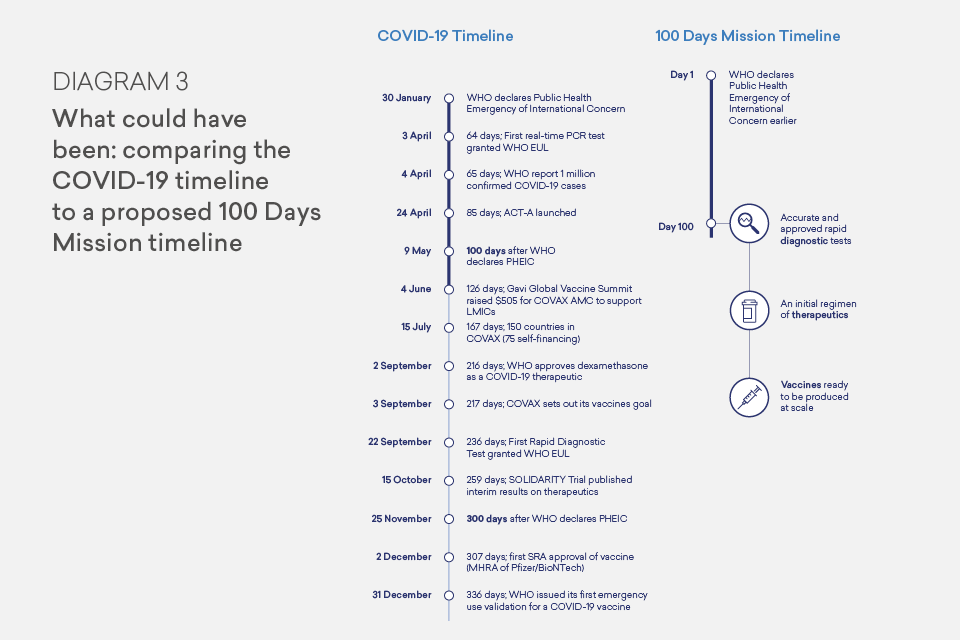

In this scenario, the world could have deployed safe and effective DTVs in May 2020, and hundreds of thousands of lives would have been saved, lockdowns would have been shortened, and trillions of dollars of lost economic output saved.

This scenario may seem far-fetched, but it is possible. We can have safe and effective DTVs within 100 days of a pandemic threat being detected. This requires preparation, investment, and a no-regrets approach. It also requires a combined and concerted effort between governments, industry and international organisations. COVID-19 showcased the capacity of our scientists, healthcare and public health professionals, industry, international organisations and the public to respond quickly. For that reason, we must be ambitious.

The first 100 days when faced with a pandemic or epidemic threat are crucial to changing its course and, ideally, preventing it from becoming a pandemic. In those 100 days, non-medical public health interventions like social distancing, isolation, contact tracing and personal protective equipment (PPE) are essential, but the three best weapons we have to defeat a pathogen threat are diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines. Together, they can save millions of lives.

Building on the target set by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) - to have effective vaccines within 100 days of a pathogen being sequenced - we propose an Apollo Mission for the modern age to galvanise the international community.

In the first 100 days from a pandemic threat being identified (defined by when WHO declares a PHEIC) we should aim for the following interventions to be available, safe, effective and affordable:

The 100 Days Mission is a rightly ambitious goal to aim for. That said, we accept the reality that for some pathogens there will be many years of work to get us to this position, but for others we could achieve the goal more quickly. A lot will depend on whether we know our enemy or if we are met with a surprise attack: whether it is a pathogen we are prepared to fight or a completely novel "Disease X" threat. And it will depend on how quickly the pathogen spreads and the severity of the disease it causes. The timing and nature of such threats is uncertain. This is why the first critical step is effective surveillance, coupled to pathogen analysis (with information- and sample-sharing). A global, integrated surveillance network can prevent us from being taken by surprise. A One Health approach is crucial, looking across human, animal and environmental health, given the danger posed by zoonotic (animal-originating) diseases, like COVID-19. We welcome the report by Sir Jeremy Farrar (the "Pathogen Surveillance Report") which calls for a network of sophisticated surveillance centres; core infrastructure to sequence, analyse data and share information; modernised sampling, governance and ethics frameworks; the use of data to drive development of DTVs; and global leadership to bring this all together, integrated with public health and academic research. This global surveillance network should inform, through clear data disaggregation for impacts by gender and race and regular foresight planning, the development of targeted and evidenced-based guidance on public health interventions for both business-as-usual responses and pandemics.

Alongside surveillance, another prerequisite of an effective DTVs response to a pandemic is strong national, regional and international health systems with clear public health protocols to respond to health threats. These protocols should stimulate, and be informed by, research and development into the transmission modes for different pathogen classes and into non-pharmaceutical interventions.

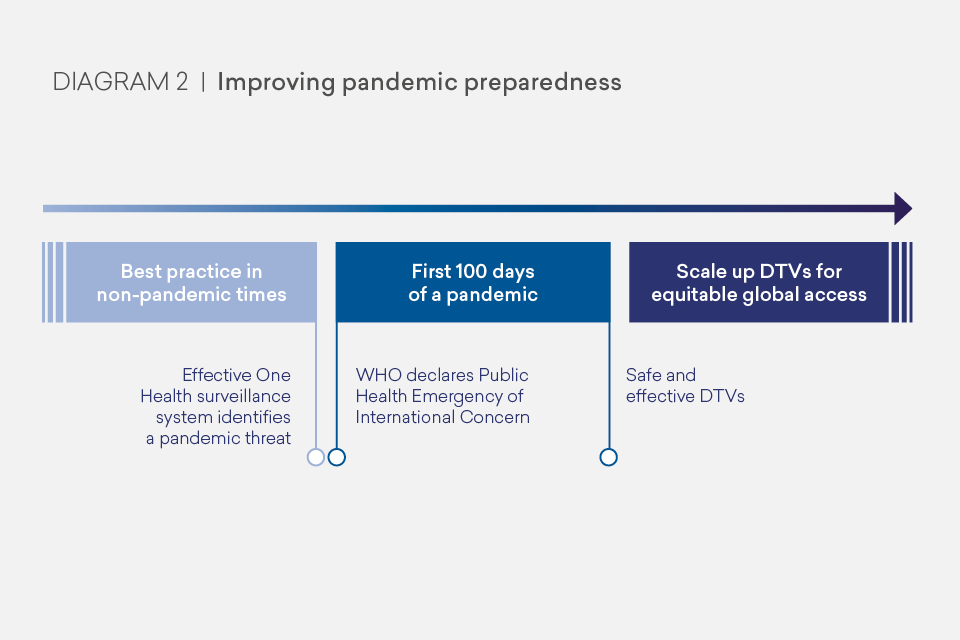

Once a pandemic threat has been identified, we need high quality validated diagnostics first, at scale, to track and help contain the infection through non-medical interventions. We should then expect therapeutics to treat the disease and prevent deaths. And we should expect safe vaccines, regulated by a Stringent Regulatory Authority (SRA) and ready to be produced at a global scale, to build immunity and prevent infection. Each of these medical tools must be designed with global use in mind and our ambition should be for equitable - needs-based - access. As shown in Diagram 2, our task is not finished at the 100 days mark; once safe and effective DTVs are available, we must be ready to scale up for global equitable access including ongoing evaluation of their implementation and impact.

Meeting this 100 Days Mission requires learning the lessons from COVID-19, as well as from previous epidemics and pandemics. First, we should acknowledge and celebrate the extraordinary advances made in this pandemic. The first vaccines were ready for clinical trials in under a month, with safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines available after a mere 307 days: an incredible achievement given novel vaccines often take up to 15 years to develop, and for some common infectious diseases we struggle to create effective vaccines at all. We are in the midst of the largest global adult vaccination campaign in history. There has been similar speed on diagnostics: automated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were available in 64 days and the first rapid diagnostic test (RDT) gained WHO approval in 236 days. In therapeutics, on day 138, we saw the RECOVERY trial report that dexamethasone, an inexpensive and widely available steroid drug, reduced the risk of death for patients with severe disease and it has subsequently saved a million lives. While these achievements must be lauded, there were - and continue to be - numerous challenges and failings that undermine our response. These lessons learned from our ongoing struggle with COVID-19, as well as previous pandemics and epidemics, highlight a number of barriers to reaching the 100 Days Mission. Key failings included: the lack of existing DTVs and low manufacturing capacity; systemic inefficiencies and inequities; and a lack of preparedness and coordination that meant there were unclear demand commitments, insufficient funding, inconsistent rules and regulations, delays and inequitable access to DTVs.

In many cases we were starting from a low base. Lack of demand for affordable, fast and accurate diagnostics before this pandemic resulted in limited research or market development. For therapeutics, there has been insufficient investment in specific and potent small molecules to treat common pathogen classes. As a result, there is an inadequate R&D ecosystem and pipeline for small molecule antivirals and "programmable" antiviral platforms. Both antiviral therapeutics and vaccines take years to develop, so waiting until a pandemic threat arises is too late. COVID-19 vaccines had a comparative head-start because vaccines against the coronavirus-caused diseases Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) were in prototype stage and mRNA technology had advanced rapidly but had never been scaled and was not sufficiently accessible to low- and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) due to cost, buy-up by high-income countries (HICs), and low storage temperatures. Manufacturing for vaccines, in particular, did not have the necessary capacity to produce vaccines at the scale required.

We suffered from systemic inefficiency and a lack of preparedness, including inadequate molecular laboratory capabilities and low capacity in supply chains and manufacturing. For diagnostics the lack of high quality regulatory pathways with clear specifications and use cases has led to diagnostics of varying quality and governments' use of tests in ways they were not intended. It took 242 days for WHO to publish its target product profile for an RDT (6 days after WHO gave Emergency Use Listing (EUL) to its first RDT). Clinical trials of treatments have often been too small, duplicative, fragmented and poor quality. For vaccines, there are continued bottlenecks in clinical trials, regulation, the availability of inputs, and scaling of manufacturing which is reducing access to those who need them. For all three areas, the response was characterised by insufficient and delayed funding, and a lack of at-risk investment driven by unwillingness to share risk, overreliance on official development assistance (ODA), and a slower multilateral development bank (MDB) response than was needed in a pandemic. This was compounded by the historical reduction in financing that is seen once health threats have diminished.

Precious time was also lost in the need to agree basic approaches and stand-up the necessary bodies. Slowness in sharing biosamples stymied the ability for industry to rapidly activate research and development (R&D), particularly for diagnostics. The Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) was set up in 85 days, and it took another 41 days for its vaccines pillar to launch the Gavi COVAX Advance Market Commitment (AMC) to provide vaccines for LMICs. While this is fast by any normal standards, it is too slow in a pandemic when every day counts. It is also worth noting that approaches and capacity for using diagnostics in tracing, isolation and border control continue to vary greatly within and between countries. Regulation has been faster than normal, but is internationally inconsistent and has been poor for diagnostics. For vaccines, COVAX will continue to be vital in enabling LMICs' access to vaccines. But it struggled to compete with HICs' vaccine purchases and was inadequately financed to provide sufficiently large and consistent demand commitments to manufacturers. This was compounded by it being not sufficiently integrated with the MDBs who could have used their balance sheets to finance procurement for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) and LMICs more quickly.

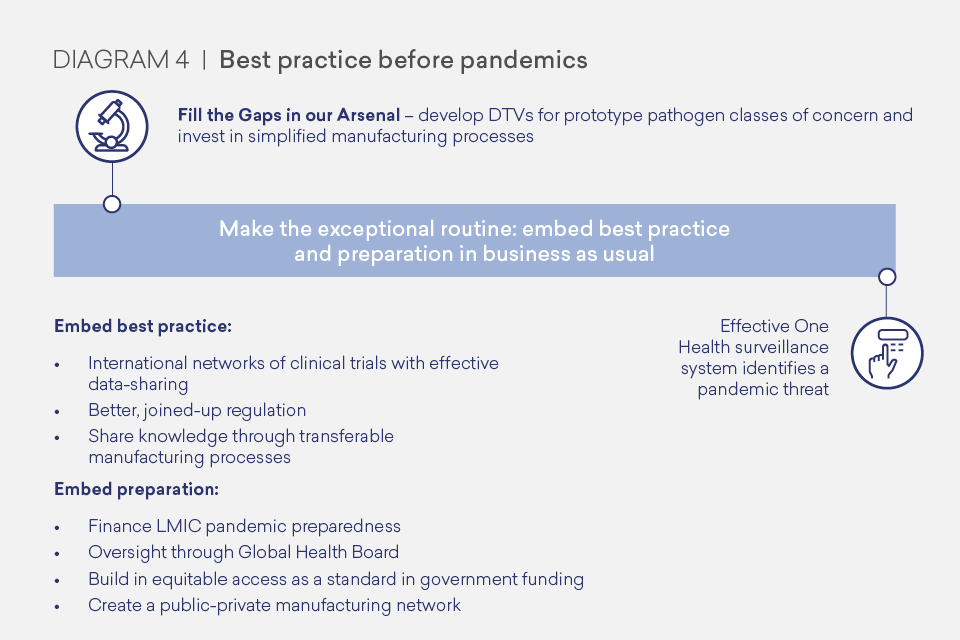

Invest in R&D to fill the gaps in our DTVs arsenal. We should have a mission-focused approach to prepare for known risks, through concerted effort and collaboration between the public and private sectors and academia. The pathogens of greatest pandemic potential are represented by respiratory viruses, but we know that viruses from at least 25 viral families can cause human disease, and in theory the next pandemic could emerge from any of these families. We can, and should, prepare prototype DTVs to treat pathogens of greatest pandemic potential and progress them to a stage that can be adapted quickly to respond to a specific pathogen threat. We must also be prepared for the unexpected, and should develop vaccines and therapeutic technologies that can be readily adapted to respond to an unknown "Disease X", including simplified and easily transferable manufacturing processes. To stimulate R&D and boost manufacturing capacity for diagnostics, we should create a market by using diagnostics as part of business as usual healthcare and surveillance. This will also improve care and help in the battle against antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Make the exceptional routine by embedding best practice and preparation in business as usual activity (when the world is not combatting a pandemic). This will not only help prepare for pandemics, but would also help in our battle against epidemics and endemic diseases. Embedding best practice as routine requires taking the best innovations from this pandemic and adopting them in day-to-day activity so that it is the norm well before a pandemic arises. This should include regionally- and internationally-networked randomised controlled trial platforms, better regulation and simplified transferable manufacturing processes, particularly for vaccines, as the norm. Embedding preparation requires international financing for LMICs' pandemic preparedness and better oversight of global health threats, bringing together health and finance expertise. It also includes maintaining readiness with networked government-industry manufacturing capacity that could be 'kept warm' in business as usual through global adult vaccination programmes.

Agree different rules of the road in a pandemic so that no time is wasted negotiating the basics. These protocols should form part of a wider suite of guidance WHO sets out (for instance, covering travel and PPE) which must be agreed in advance and demonstrate a step-change from business as usual when a PHEIC is declared. This trigger relies on a more rapid and nuanced PHEIC declaration process. For DTVs, these rules of the road should include guidance on supply chains, indemnification and data sharing as well as a system to share data and biosamples, and utilise standardised assays. Pandemic response needs to work through existing international institutions, with the rules of the road activating a step-change in behaviour that complements the best practice and preparation established between pandemics. We would then be ready to enable rapid prioritisation, speed, scale and equitable access including activation of networked manufacturing and clinical trials, automatic DTVs financing and rapid, joined-up regulatory approvals processes with pandemic-appropriate guidance.

With a 100 Days Mission providing focus, the crucial steps that governments, industry and international organisations must take to improve our pandemic preparedness are set out below. The full list of recommendations is set out in Annex A and the detailed thinking is set out in Chapters 2-5. These recommendations will need to be underpinned by sustained financing ahead of a pandemic to achieve our 100 Days Mission.

Industry and academia should prioritise R&D into diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines against the WHO list of priority pathogens, and, within this list, the respiratory viruses coronavirus and influenza, given their propensity to cause pandemics. We should aim to have prototype DTVs against the virus families of greatest pandemic threat. For instance, preparing a pan-coronavirus vaccine or antibody therapies that can be adjusted if a deadly form of coronavirus appears again. Similarly, we should embed simplified transferable vaccine manufacturing processes as the norm. The main route for this effort will be the private sector, with research from academia and supported by the public sector and international organisations - it will also require new partnerships or ways of working, as well as enhancing current approaches. In this regard, we believe expanding CEPI, which currently focuses on vaccines, will fill a crucial gap in the international system in providing R&D funding and coordination for therapeutics and diagnostics. CEPI is already planning to use a financing model inspired by Gavi's International Finance Facility for Immunisation model (IFFIm), which allows donors to frontload financing. CEPI should explore further sources of public and private financing and funders should look to meet CEPI's funding asks, including at the CEPI replenishment conference in 2022.

Industry, governments and international organisations, should explore how a vaccine manufacturing network, utilising the latest technology, could be rapidly activated in a pandemic. Governments and international organisations should also consider expanding mass adult vaccination campaigns for common diseases - both to respond to very real and pressing public health needs and to create regular demand for expanded capacity. An expanded vaccination programme would have widespread health benefits and would help address the need to 'keep warm' manufacturing and stimulate innovation in business as usual, while avoiding the trap of public money paying for empty facilities that soon become outdated. Group of 7 (G7) governments should also consider normalising the use of diagnostics as part of enhanced surveillance and at points of care for cost-effective use cases, which will stimulate and maintain the market. FIND, the global alliance for diagnostics, has a key role to play in ensuring access to diagnostics for developing countries by 'match-making' between industry and demand.

WHO should work with governments and stakeholders to scope an international clinical trials network to enable a coordinated and efficient approach to testing of new DTVs and existing therapeutics. The network should bring together national clinical trials infrastructure, interlinked regionally in a way that can be rapidly commandeered as a global resource in a pandemic. The network should enable immediate and transparent knowledge and information sharing, with appropriate confidentiality protections and clear data disaggregation standards for impact by gender and race at all stages of analysis. It will require baseline funding from countries to strengthen their own clinical trial infrastructure and create regional links, supplemented by a "user-pays" model (whether academia, public sector or industry). This clinical trials network should always be active (including between pandemics) and be able to rapidly refocus in a pandemic or epidemic, supported by a mechanism to prioritise which DTVs products to trial. Regulations should allow easy moving of clinical trials across the network at a speed that matches the migration of any epidemic or pandemic around the globe. In practice this means having clinical trials infrastructure owned in countries and networked first at a regional level.

SRAs, working with WHO and other relevant organisations, should streamline, harmonise and simplify regulatory processes in business as usual, and agree a faster and joined-up approach in pandemics. This review should include a new look at existing rules such as the Good Clinical Practice guidance for clinical trials and consider whether they are still fit for purpose. SRAs should prepare target product profiles prior to a pandemic being declared by WHO — with preferred characteristics set out by type of pathogen that may emerge or spread uncontrollably. It should also consider the development of risk-adjusted, scenario-based approaches to accelerated approvals or emergency use authorisation as soon as a DTV is shown to be beneficial.

WHO should work with governments, other international organisations and industry to set rules of the road for pandemics, including for supply chains, indemnification and data sharing. This guidance should set out expectations on shifting from business as usual and enable speed, scale and equitable access. Part of the rules of the road should include automatically activating a DTVs financing facility, which could be made up of a series of pre-negotiated, pre-funded advance commitments. This will provide demand signals to pharmaceutical companies and ensure sufficient supply is made available quickly in a pandemic, including to LMICs, based on clinical need.

Companies should, in exchange for some risk-sharing from HIC governments, commit to providing diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines at not for profit for LMICs when a PHEIC is declared. This must also be done within a similar timeframe to when HICs are supplied. HICs should make this a condition of Advance Purchase Agreements (APAs) during a pandemic. In business as usual, HICs should include equitable access clauses in their funding agreements for DTV R&D, manufacturing or other early push funding. These clauses should require production of the diagnostic, therapeutic or vaccine at not for profit and scale during a pandemic or epidemic situation. This should ensure that public money funds public good and continues to support innovation.

A Global Health Board should be set up under the auspices of the G20. This would be for the G20 to establish; we suggest the Board could report to a joint session of Health and Finance Ministers on an annual basis on ongoing and emerging risks to the international system from pandemic threats, and actions needed to address them. The G20 should consider including in the Board the three Chief Scientific Advisers (CSAs) or their equivalents (e.g. Chief Medical Officers) and Finance Deputies of the incumbent, previous and successive G20 Presidencies, the One Health Organisations, The Global Fund, Gavi, CEPI and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. It could be chaired by WHO, with the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) acting as the secretariat, to provide independence, expertise and stability to the Board. By reporting directly to the G20, the Board would be well placed to stand up the necessary response quickly to a PHEIC, and should expect the full-political and financial backing of the full G20 membership.

This report represents recommendations by the partnership for pandemic preparedness to the G7. The partnership was formed by public and private sector experts on the request of the UK's 2021 Presidency of the G7. It is informed by the ongoing response to COVID-19, as well as the response to epidemics and endemic diseases.

Given the number of other vital reports and reviews of the COVID-19 response (including, but not limited to, the WHO Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response [IPPPR] and G20 High Level Independent Panel), this paper is consciously focused on a specific part of the puzzle: the critical medical tools of diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines. Other elements where separate attention would be welcome include non-medical interventions and health system strengthening. The members of the partnership welcome the report by the IPPPR and its contribution to the international debate. And while we applaud the noble goal of the IPPPR that COVID-19 be the last pandemic we face, we believe the science and evidence suggests we must prepare for the worst and - in doing so - make it less likely.

Source: 2021 G7 UK Presidency website

[back to top]

—

|

This Information System is provided by the University of Toronto Libraries and the G7 Research Group at the University of Toronto. |

|

Please send comments to:

g7@utoronto.ca This page was last updated June 12, 2021. |

All contents copyright © 2024. University of Toronto unless otherwise stated. All rights reserved.